Following my last post, Budget Season is Here, I did a bit more digging into Winnipeg’s history of taxation and budgeting. That means you, dear reader, get another post about property taxes. My apologies in advance, for the subject and the necessity of a long post!

The Fiscal Imbalance

When last we left off, I made the argument that municipalities are operating with “one hand tied behind their backs” when it comes to revenue generation. They really only have one tool, that being property taxes. That limited ability to raise revenue results in municipalities receiving less than 10% of all taxation while being responsible for 60% of all public infrastructure. That is a significant fiscal imbalance that municipalities right across Canada have been decrying for years.

Tying Themselves Up

While the City of Winnipeg has been operating with one hand tied behind its back because of the fiscal imbalance it has even more firmly tied the other hand themselves. While the City of Winnipeg is continually seeking more money from the provincial government, at the very same time they are doing little to use the one tool it does have: namely property taxes.

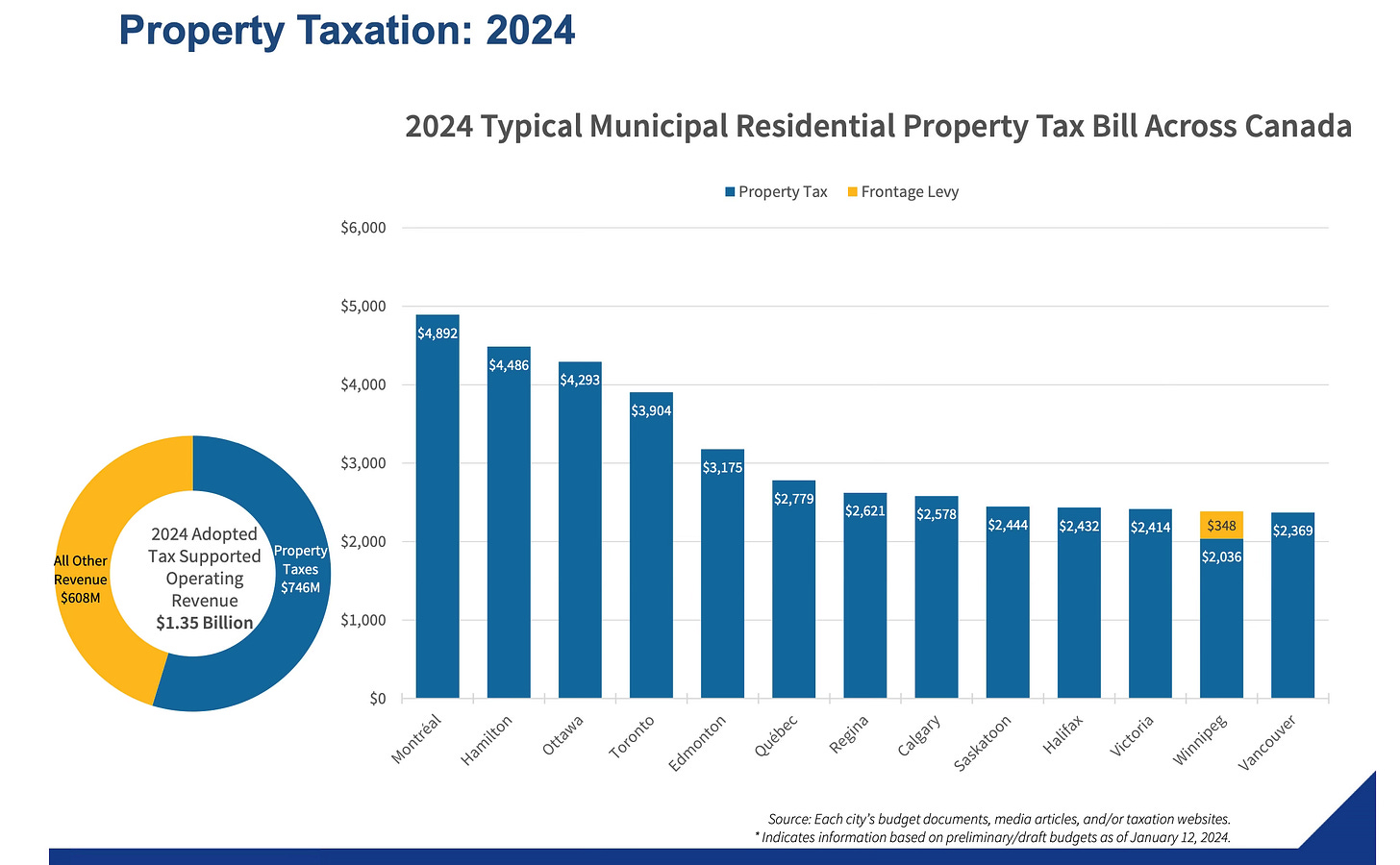

Every year, the City of Winnipeg and City Council proudly trumpet that Winnipeg pays the lowest property taxes in Canada! It’s true, any way you look at it, Winnipeg pays the lowest taxes.

“a typical Winnipeg homeowner will now be paying less in municipal property tax – including frontage levies – than the owner of a comparable home in every other major city in Canada.” - City of Winnipeg Budget 2024-2027

Ironically, the very next paragraph in the Budget lays out that it needs more money, and it is looking to the Province of Manitoba to provide it, literally passing the buck!

“However, the City will still need more revenue in the years to come, both to protect service levels and to modernize operations, software and equipment. With this in mind, we continue to seek growth revenue options and transfer reforms through collaborative discussions with our partners at the Province of Manitoba.” - ibid

On the one hand…

The City of Winnipeg proudly says it has the lowest taxes in Canada. It is a designation it has wilfully chased for decades, beginning back in 1998 when City Council imposed its first tax freeze. Since then, with year over year of tax freezes, it has become the cheapest city in the country. Almost every budget proudly contains a chart like this one:

On the Other Hand...

At the very same time, City Council says it just doesn’t have enough revenue to deliver services and needs the Province to bail them out. And yes, as I have argued before, Winnipeg needs a new fiscal relationship with provincial and federal governments. I would also argue in Winnipeg’s case for more fiscal tools would be stronger if it was actually using the tools it already has effectively

The slow road to being the worst

While City Council would like us to believe that having the lowest property taxes in the country makes us the best, looking around at the quality of services being delivered to Winnipeggers, it is clear that it has made the city the worst. From snow clearing, the disappearing urban canopy, the quality of sidewalks, responsiveness to 311, to the state of our streets, the state of Winnipeg’s public space is the abject reflection of what being the cheapest, and worst, looks like.

Fixing this is going to take time, just as it took City Council decisions, year after year, to get us to this deplorable state. And yes, the state of Winnipeg is deplorable. I have been to most of Canada’s “Big Cities”, and I can unequivocally say that Winnipeg’s downtown is in the worst condition of any of them. From the amount of garbage around, to the broken sidewalks, empty planters, and general upkeep, Winnipeg is the embodiment of what decades of “austerity” budgeting looks like.

This all started back in 1998, when City Council decided to impose its first tax freeze. That continued until 2012, when Council decided to increase taxes for the first time since that freeze. Even worse, under Glen Murray there were three years of 2% tax reductions. Starting in 2012, City Council has implemented tax increases each year. But, as we shall see, the fiscal hole was already dug and what they were doing wasn’t making it any better.

How to think about property taxes

Property taxes generally pay of the operating of the city. The cost of employees, fuel, operating buildings, maintenance of parks & sidewalks, snow clearing etc. are all paid for by property taxes. Capital budgets, the stuff we build, are generally paid for through debt and grants from other orders of government. A good way to think about this is transit: the busses and garages are paid for through capital, which in Winnipeg is almost exclusively from the federal government, whereas the bus driver is paid for through property taxes.

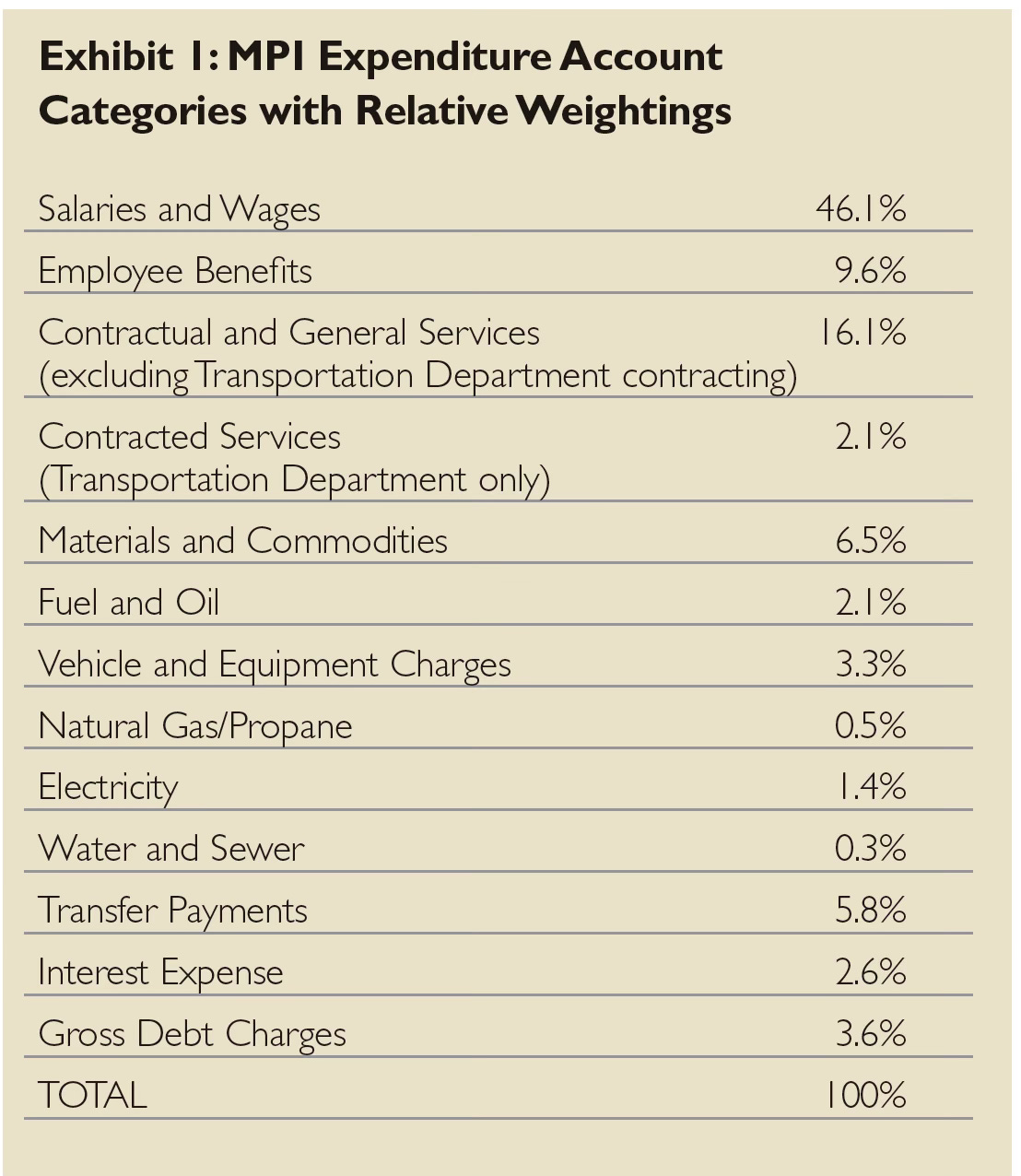

Operating a city gets more expensive every year. Gasoline goes up, hydro goes up, employees get raises and so on. The city’s cost of operating increases year over year, just like everywhere else. For people, this cost-of-living increase is quantified each year as the Consumer Price Index (CPI), or the rate of inflation. Cities have tried to estimate what their “cost of living” is through a tool called the Municipal Price Index that reflects the “basket of goods” that cities buy, which are different than what people buy. There is no standardized method for this yet, but when studied it has generally tracked above the CPI.

For our purposes, we are going to stick to tracking the CPI from Statistics Canada to help us understand the increasing costs of operating the city.

One other factor that goes into increasing the costs of operating a city is growth. Each new resident requires more services. You need to increase transit, police service, fire service. How we have been growing Winnipeg, and every other North American city, over the past 50 - 75 years is through expanding our suburbs. We build new communities on the edges, needing new roads, more water treatment, more parks, and sometimes, if you are lucky, more sidewalks to be cleared. All those things increase the cost of operating the city.

Yes, those new people provide more property taxes, but those taxes don’t cover the cost of operating that new subdivision. As well, the city needs to provide services as soon as people are moving in, before the “tax base” is established. You can’t wait until all the houses are built before you provide snow clearing or police service.

Every year, year over year, the operating cost of the city goes up. Operating costs mostly paid for by property taxes. Property taxes that have either been frozen or not kept up with inflation since 1998.

Digging the hole deeper

Council started digging the hole in 1998 and haven’t stopped digging since. Even with the current proposed tax increases of 3.5% they are still digging it deeper. And just like compound interest, it is a compounding deficit.

Taking 1998 as starting point, the fiscal gap for providing services has only grown. That first year with the tax freeze, the rate of inflation was 0.8%. The lowest rate of inflation in the past 25 years. The gap of operating revenue, property taxes, not keeping up with inflation was only 0.8% that first year. Easily absorbed. A great political decision with little financial impact and probably no direct impact on services.

But, the pattern continued. 0% increase the following year, and the year after that, and so on. All the while, inflation is increasing costs year over year, by 1.8%, 2.5%, 2.8% and so on. The fiscal gap that was manageable in year 1, is now compounding and only getting deeper. It now begins to impact services: less road maintenance, less clean up of parks and sidewalks, less snow clearing, decreased transit service, and so on.

When you take those yearly decisions of freezing taxes, reducing taxes, or not increasing them at the rate of inflation over 25 years into account, that compounded fiscal gap gets to be pretty significant. What started out as a 0.8% gap between operating revenue (property taxes) and operating costs in 1998 had become a 66% gap in 2023. What was an unnoticeable change in 1998 has now resulted in a city that few people are happy with. Recent poll: Everything is Getting Worse

For the fellow data geeks, here is the spreadsheet laying all that out. Data collected from Statistics Canada and City of Winnipeg.

Winnipeg is Cheap

One other way to look at the municipal budget and what the City has to operate is to look at how much the city raises through taxes per capita. This is a good indication, because as we see, property taxes pay for the operating costs of a city. The city is not allowed to run a deficit which means that its operating revenue must cover its operating costs. Low taxes means low operating costs, and the only way to achieve that is through cuts.

Property tax per capita is indicative of what it spends on delivering services. In this regard, Winnipeg once again proves to be incredibly cheap, receiving (and spending) less than $900 per person. By comparison, the city we most like to compare Winnipeg to, Edmonton, receives $1,737 per person. Almost double Winnipeg.

In 1998 property taxes made up 58% of the City of Winnipeg’s revenue, in 2024 that is down to 35%. While every city has worked to decrease their reliance on property taxes and shift towards user fees and sales, Calgary, that most fiscally conservative of cities, is currently at 45% of its revenue coming from property taxes. (maybe a post for another day to look at the wisdom of the shift to user fees!),

The Hole is Deep

Let’s face it, promising to not increase your taxes is a (short term) political winner! We are sacrificing our future to win points today. But those decisions combine and grow. Over time they become almost insurmountable. The fiscal hole that Winnipeg finds itself in today requires leadership and a willingness to make different decisions.

We need to stop digging the hole deeper. Rather than simply going to other orders of government seeking more money, City Council needs to actually show it is willing to begin addressing its fiscal challenge itself. If they demonstrate a willingness to make better decisions, both on revenue and expenditures, then they would have a considerably stronger argument when they sit down with the provincial and federal governments to address the fiscal imbalance.

But we need to stop digging first!!

brian